Analyzing a companion app for a cheap Chinese IR camera

I recently got recommended a video by Dmytro Engineering about his journey with reverse engineering the Xinfrared Xtherm II T2S+. In it, he mentions how the app requests an insane amount of permissions (a short list is in his blog post), including a few used by malware, such as SYSTEM_ALERT_WINDOW, WRITE_SETTINGS, CALL_PHONE and others.

While his video was interesting, I was left wondering how exactly this permission abuse is used in practice. He theorizes that maybe an incompetent developer slapped on permissions until the app stopped complaining. I think that is indeed the case, and I will describe why in this post.

Because I don’t have the camera, I can’t test the app extensively. Most of my conclusions are drawn from static analysis. Also, while I did my research, I may have missed or misunderstood some things. I’m not an Android RE pro, I just like poking around apps for fun

The Android permission model

To understand how severe this really is, one must first understand how Android permissions work.

Before an app can take a certain protected action, it must declare in its manifest the permission for it. This prevents apps from having full control over the device and allows the user to inspect, and in some cases control, what an app does to the system.

There are three main types of permissions:

Android categorizes permissions into different types, including install-time permissions, runtime permissions, and special permissions. Each permission’s type indicates the scope of restricted data that your app can access, and the scope of restricted actions that your app can perform, when the system grants your app that permission. (source, emphasis mine)

- Install-time permissions: are implicitly accepted by the user when installing the app. Includes actions like network access, running on boot, running license checks with Google Play, etc.

- Runtime (dangerous) permissions: are denied by default and can be requested while the app is active. Examples: storage, camera and location access.

- Special permissions: are similar to dangerous permissions, but are separated for being particularly sensitive or powerful, like drawing over other apps or modifying system settings.

Most permissions that users consider sensitive can only be enabled with an user interaction and can be rejected if the user wishes to do so. Just because it’s in the manifest doesn’t mean the app will have the permission right away.

Regardless of the permission type, it must be declared in the manifest. If a permission that isn’t there is requested, the app will crash. Because of this, some developers declare permissions without ever requesting or using them - perhaps for planned features or as a precaution.

The app’s permissions

This is a non-exhaustive list, here’s all of them from the manifest itself. There are a lot of duplicates, but in total <uses-permission> is used 47 times.

- Special: manage MDM settings; show over other apps; change system settings

- Runtime: access fine and coarse permissions; read images, audio and video from media folders (Android 13+); read external storage (up until Android 13); use the camera and microphone; make phone calls;

- Install-time: access the internet; modify internet connection state and settings;

- Unknown:

android.permission.AUTHENTICATE_ACCOUNTS,android.permission.USE_CREDENTIALSandMANAGE_ACCOUNTS(not in Android since 6, which is also the app’s minimum version);android.permission.GET_TASKS(deprecated since Android 5)

Most of them are runtime permissions. But how many of them does the app actually request and use?

Analyzing the decompiled code

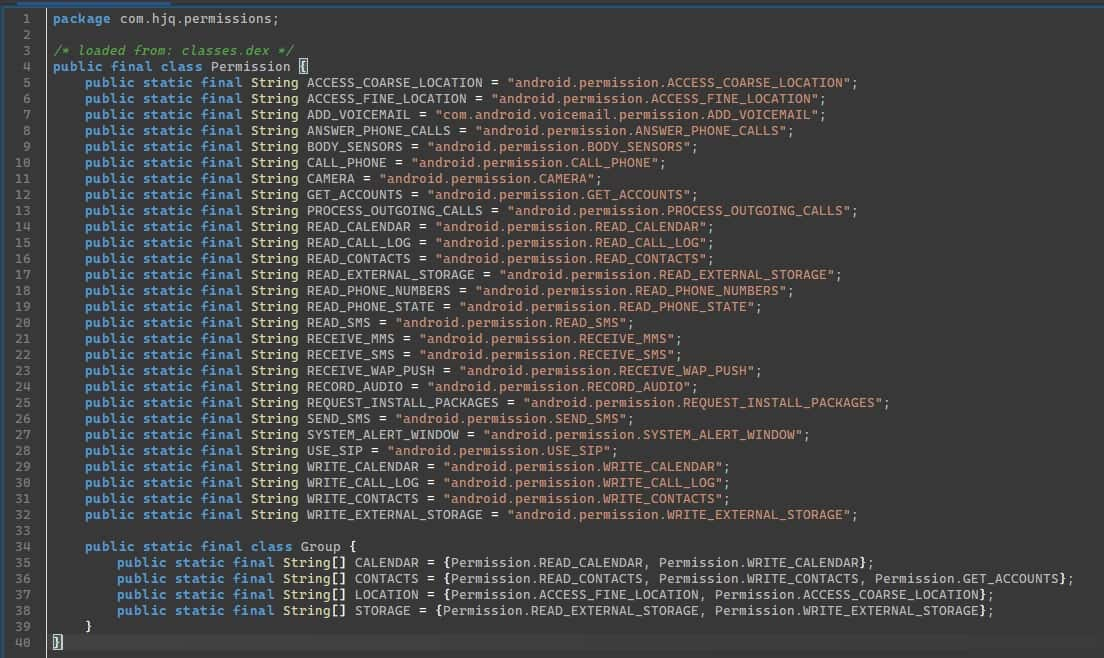

The app has no obfuscation whatsoever. JADX can decompile the entire app flawlessly - no “code decompiled incorrectly” errors that usually plague its output. Using JADX’s search, I looked for any code containing the word “permission” and found a class conveniently named “Permission”

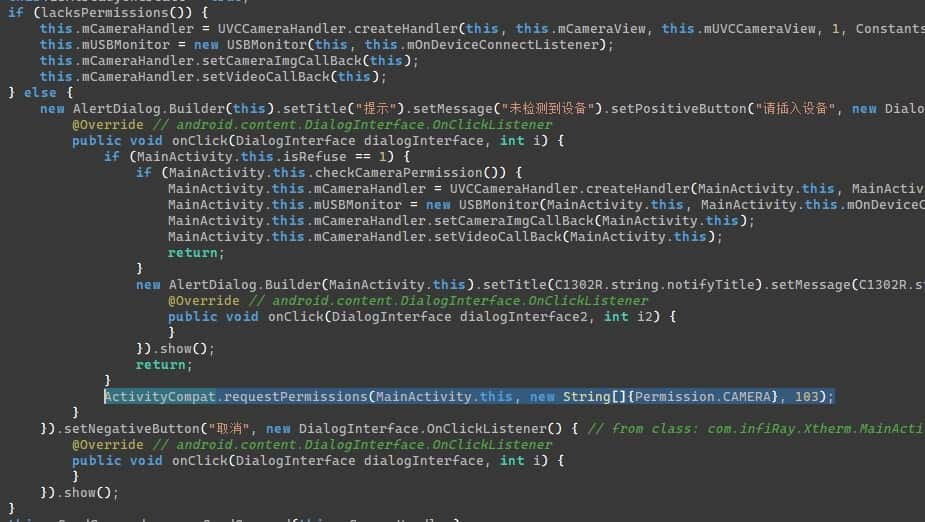

As I wasn’t familiar with how apps request permissions (there are various ways), I thought checking the usage of CAMERA would be a good way to find out where they are requested. Indeed, it leads me to this bit of code:

The rest of the code isn’t too important, it basically checks if the app has the needed permissions and requests them if it doesn’t. But now that we know how the app makes the request, we can search for places where the function is called, and subsequently what runtime permissions the app uses.

Out of all the declared permissions, the only ones the app requests are:

android.permission.READ_MEDIA_*andandroid.permission.CAMERAin the main activity, makes sense for a camera appandroid.permission.ACCESS_*_LOCATIONfor geotagging, more on that in a bitandroid.permission.WRITE_EXTERNAL_STORAGEincom.zhihu.matisse.internal.ui.BasePreviewActivity, unsure what this is aboutandroid.permission.CALL_PHONEincom.infiRay.Xtherm.ui.Personal_Centerfor… something?

CALL_PHONE???

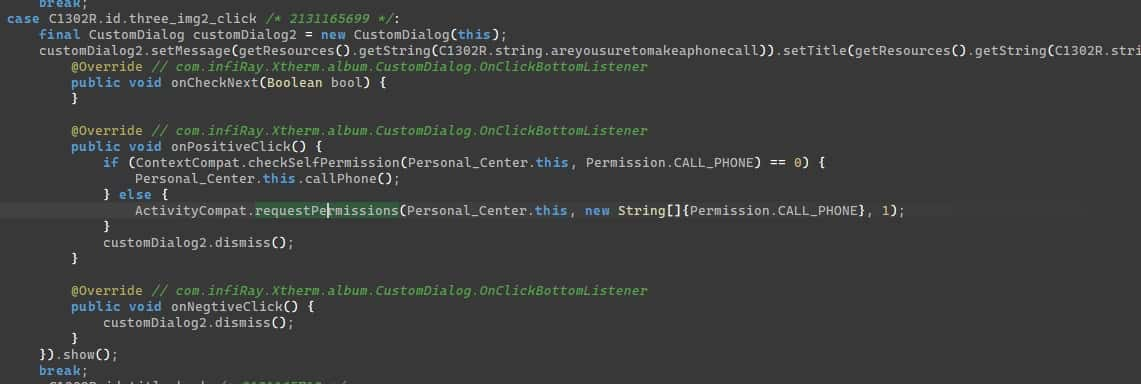

Why does this app need to make calls? I investigated further.

The method this call is made from is an on click event handler:

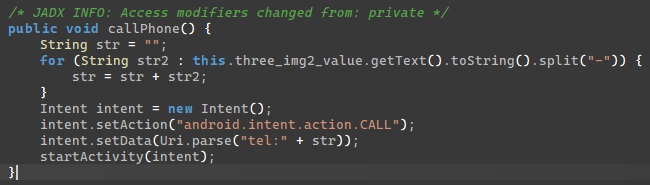

If the app can make calls, it runs the following code:

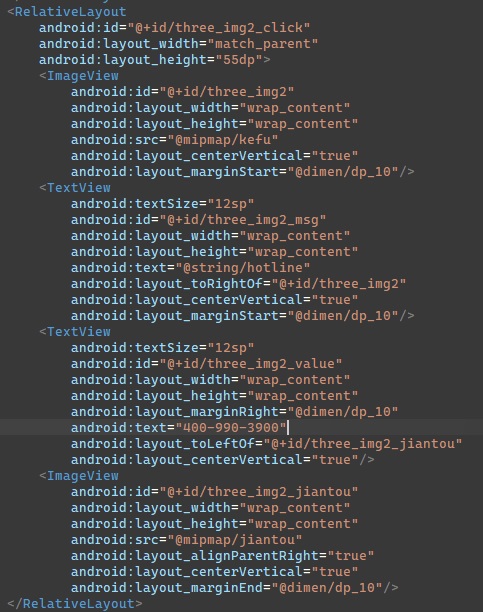

So it seems to read the text of an UI element and use it as a phone number. I located three_img2_value inside res/layout/java_login.xml

Googling the phone number, it seems to be a Chinese hotline for Xinfrared customer support.

How can the user reach this login screen? com.infiRay.Xtherm.ui.Personal_Center is referenced in com.infiRay.Xtherm.ui.Set (conflicts with the built-in type and confuses JADX, lol) as a login page. Set is then referenced in the main activity, in a bit of code that runs when the settings button is pressed. So, judging purely by static analysis, you can call Xinfrared by going into the app’s settings and finding a login button somewhere.

Is that it?

Not quite. I found some other worrying stuff.

- The code sucks, but Dmytro already said that.

- On app startup, it initializes some Baidu geolocation SDK and tells it that the user has agreed to some sort of privacy policy, despite never actually requesting the user’s consent. In the background, the app listens and saves the user’s province, city, latitude, longitude and altitude.

- This data does seem to be used for geotagging (

com.serenegiant.usbcameracommon.AbstractUVCCameraHandler.handleCaptureStill), but only the lat/long and altitude. You don’t need a third party SDK to get that info.

- This data does seem to be used for geotagging (

- If the app was still on the Play Store, the usage of those permissions could change at any moment. For example, the app asks to start when the phone starts up, but never sets a receiver class for that event. An update could change that, and it’d have all the permissions the user gave it before the update.

- There are mentions of some analytics SDKs in the code, but at this point every app on earth is full of them so I won’t even bother talking more about it.

Conclusions

The fact the app declares so many permissions but uses very few of them and the numerous duplicate <uses-permission> tags in the manifest brings me to three theories:

- A case of a clueless developer pasting random shit from Github, ChatGPT or Stack Overflow in a lazy attempt at getting the app to run.

- A developer wanting to get past the Play Store’s verifications for sensitive permissions early so they can do bad stuff later. I don’t think this applies here, since the app can be downloaded directly from their website.

- A side effect of how the Android build system merges library manifests into the main app manifest. Can be ruled out as

<uses-permission>is merged during app build, which should hide duplicate permissions from libraries. The duplicates must’ve been added manually.

I think this is a good example of how not to work with Android permissions. If the Play Store listing was still up, all those permissions would likely be visible under the app’s details. It’s not a good look for your product when your basic camera app wants to change system settings.

As for whether or not the app is safe to insall, I’d say right now there’s no cause for concern for the average user, but caution is still necessary. Again, an app update can change how the permissions are used. No one knows when, or if, Xinfrared might upload a trojan intentionally or by accident.